Creatures of Chaos

Creatures of Chaos

Hannah V.M. Stewart

On the Contrasts of an Ordered Creation and Our Disordered Lives

What has been will be again, what has been done

will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.

— Ecclesiastes 1:9

Little snail,

Dreaming you go.

Weather and rose

Is all you know.

Weather and rose

Is all you see,

Drinking

The dewdrop’s

Mystery.

— “Snail” Langston Hughes

“Look! It’s a pattern!”

The words come from a little mouth missing one of its front teeth, with big blue eyes above, and wispy blond curls all around. I’m working with a kindergartener on counting by 8s, 9s, 11s, and 12s. Around us, fluorescent lights shine on white walls coated with cartoon math figures—an equilateral triangle does pushups on one wall; across from the triangle, a set of percent and division signs fly high on swings; in the background, Mozart’s Piano Sonata in B-flat major plays. Lucy’s just discovered that when she counts by nine beginning at zero, each number’s digits will total nine. The pattern is like candy; she’s addicted at first taste. She tries her trick on the next problem, this time counting by elevens. The pattern’s more elusive, but she deciphers that when the digits are added together, they go up by two.

I watch wonder flood her eyes. With every pattern her giggles get louder, she grips her yellow-orange crayon tighter, the world seems to dance into her hands. Once, it appears, a sequence has an anomaly. The sums that were counting by two all the way up to nine suddenly plummet back to three.

“But that doesn’t make sense! Why is there a three? It should be an eleven!”

She scrubs the ink with her eraser.

“We need to make it go away! It doesn’t belong.”

“Try the next number,” I suggest.

She discovers the pattern has simply restarted from the first number. Her red cheeks turn pink again in excitement.

“You are a mathematician,” I say.

She smiles, nodding, “My teacher calls me the same thing.”

The patterns give her power. Because she knows the rule, she can predict. When she predicts, there is nothing she cannot do. She’s beginning to understand the laws that govern life.

“I think that’s pretty hard, what I did. Because it’s so tiny and maybe a lot of people wouldn’t know to see that,” she concludes. She picks up the bubblegum crayon to use for her next problem.

“That’s how people make big discoveries,” I say. “By looking at very small details. You’ll discover something big someday, Lucy.”

*

A leathery snail drools along cracked pavement, oozing as I nearly crush it. I’m running on a drizzly Saturday morning. I catch the brown of its shell in the corner of my eye and quickly veer. All around me is the green and dark lush of Seattle. I pass a succulent, infinitely emanating from the mossy ground. These sights are more than scenic—they point to an underlying order.

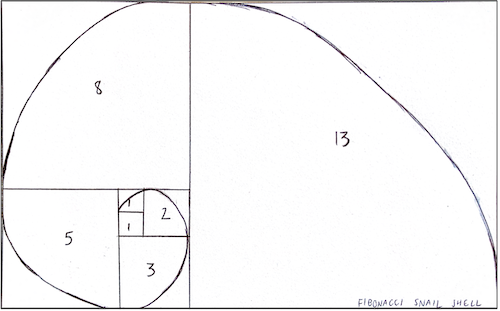

If you ask the Earth about the secrets in her core, she’ll whisper them to you: the snail’s shell is perfectly mathematical. If you were to draw two equal squares next to each other, and one big one next to them the size of the small ones combined, and you continued drawing bigger squares around them, you’d get a snail’s shell. The squares’ dimensions form the Fibonacci sequence: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 and so on. The infinite succulent, Aloe polyphylla, also lives by these numbers; its leaves form the Fibonacci sequence, allowing the plant an abundance of growth and sunshine. The pattern bearing an Italian mathematician’s name is found in plants and snails and peacock tails and butterflies and chameleons; creation is ordered, patterned, discerned, and predicted. It is natural that we, like Lucy, seek out these patterns.

The Earth asks us to join her rhythmic dance. We do, each time we speak a word. The English language has exactly seven patterns for every sentence. No matter how many words or clauses, each sentence fits into one of these seven boxes. Every number we can imagine breaks into a finite set of prime numbers. Pythagoras once said, “there is geometry in the humming of the strings.” Music is woven together by math. Its threads, melodies, made of measures, made of beats, are infinite. Patterns continue into the instruments that hold these melodies; eight of the keys in a piano’s octave are white, five, black. The black keys are further grouped into sets of two and three. This is the Fibonacci sequence at play. The patterns are enticing, seductive even; we cannot help but align ourselves with them.

Across countries and cultures, our days our divided as though we are one, uniform being. On average, we spend eight hours working, one and a half hours eating, two hours doing things for leisure, and the remaining thirteen and a half hours sleeping and going to and from. The sun rises and sets, telling us to do the same. The patterns in creation fashion our own. We cannot divorce ourselves from the very ritual of living.

It’s comforting to think we live in a world that behaves. A world where certain inputs result in certain outputs. Where 1 + 1 = 2 and the sun is a star. It’s also empowering. All the systems we’ve set up to predict tomorrow—weather channels, stock markets, population studies, climate trends—let us conquer that one last forbidden territory, the future. When we grasp the future, we become like God. That’s what makes patterns into the sweet candy Lucy tasted.

But our patterns are frail. And so, our predictions, our scribbles of tomorrow, are too. The neutron, proton, and electron gave way to quarks and leptons. Copernicus’s theory took nearly a century to become accepted. Our world continues to split into smaller pieces and orbit in ways we’d never thought. Behavior that is not predicted, not expected, not supposed to be, happens all the time. In humans, in nature, in our planet, in our solar system. Like Lucy, we are tempted to erase the ink from the page. But like Lucy, we keep looking for the next number. And we make a new pattern.

We find birds and bears in the stars and name them constellations. I find these same constellations in the freckles on my face. Wherever we are under the forever turquoise and red and purple sky, we want it to mean something. Apophenia, from the Greek, a term coined by German psychiatrist Klaus Conrad, describes our condition: “the tendency to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things.”

Without the numbers that promise us nothing more and nothing less than infinity, we humans, the creatures of chaos, cannot survive.

*

I watch a striped onesie and head full of brown hair. He’s a little older than a year. His hair is fluffy, like he’s held a balloon to it. The little boy makes his way across a pew; his dad is up front, playing drums. The boy wears a grin, crawling to the edge of the pew, despite his mom picking him up and plopping him back where he belongs again and again. Every once and a while, she’ll point to his dad, who the boy claps for with sticky, stubby hands. The boy’s grin flickers on and off like the sun passing through clouds. He sneaks across the plush red pew once again.

I cannot help but smile through the songs. This little boy in front of me, knowing no boundaries of the world, of himself, is enough to make anyone float. Sunshine streams through the stained-glass windows. It is a warm Sunday morning and the air smells like grass and just-born sparrows. Life is abundant and shiny and new.

I don’t see the boy or his parents for a while. I figure they’ve gone on a trip. Two weeks later I hear from the pastor.

The boy’s parents found him dead in his crib. His death is described as SIDS. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. My mother, a doctor, numbers four ways of dying: not enough oxygen, too high a temperature, chemical poison, or physical damage. The boy’s parents leave the house the next day.

We lie in the chasm between what should be and what is. We die at the hands of the very patterns that give us breath, the patterns that fail us time and time again.

*

I walk by the Puget Sound, inhaling its waves as they crash against the shore. Its deep blue belly moves in and out. I follow its breath. Waves crash. Breathe in. Waves recede. Breathe out. In and out, in tune with the salty air. I hear God weep in the rain that falls. I hear God laugh in the sparrows that sing. I stand under this smiling, crying, God, and I think of the little boy, his hair and grin, his parents who have lost the world.

I think in these moments, when we ask why why why, why God? why me? why him?, we really mean to ask what. What do we do when our heart is a stone within our chest? What do we do when our eyes, like Job’s, “have grown dim with grief,” and our “whole frame is but a shadow”? What do we do when the world that has promised us its patterns withholds?

We ask what and we weep. We weep until we, like all created things, heal. And when we are ready, we ask why. We ask why and we grasp the shell of the snail, the purple of a lily, the spots of a butterfly.

Hannah V. M. Stewart

Student & Writer

Hannah has published a fiction short story and poem in Body Without Organs. She is an undergraduate student preparing to be an elementary educator. Writing has always been the way Hannah makes sense of this world; she hopes to continue to make sense of it– through the children she works with, and the words she finds along the way.

To view more of Hannah’s work, visit https://hannahvstewart.weebly.com.

Photography by Martin Vysoudil