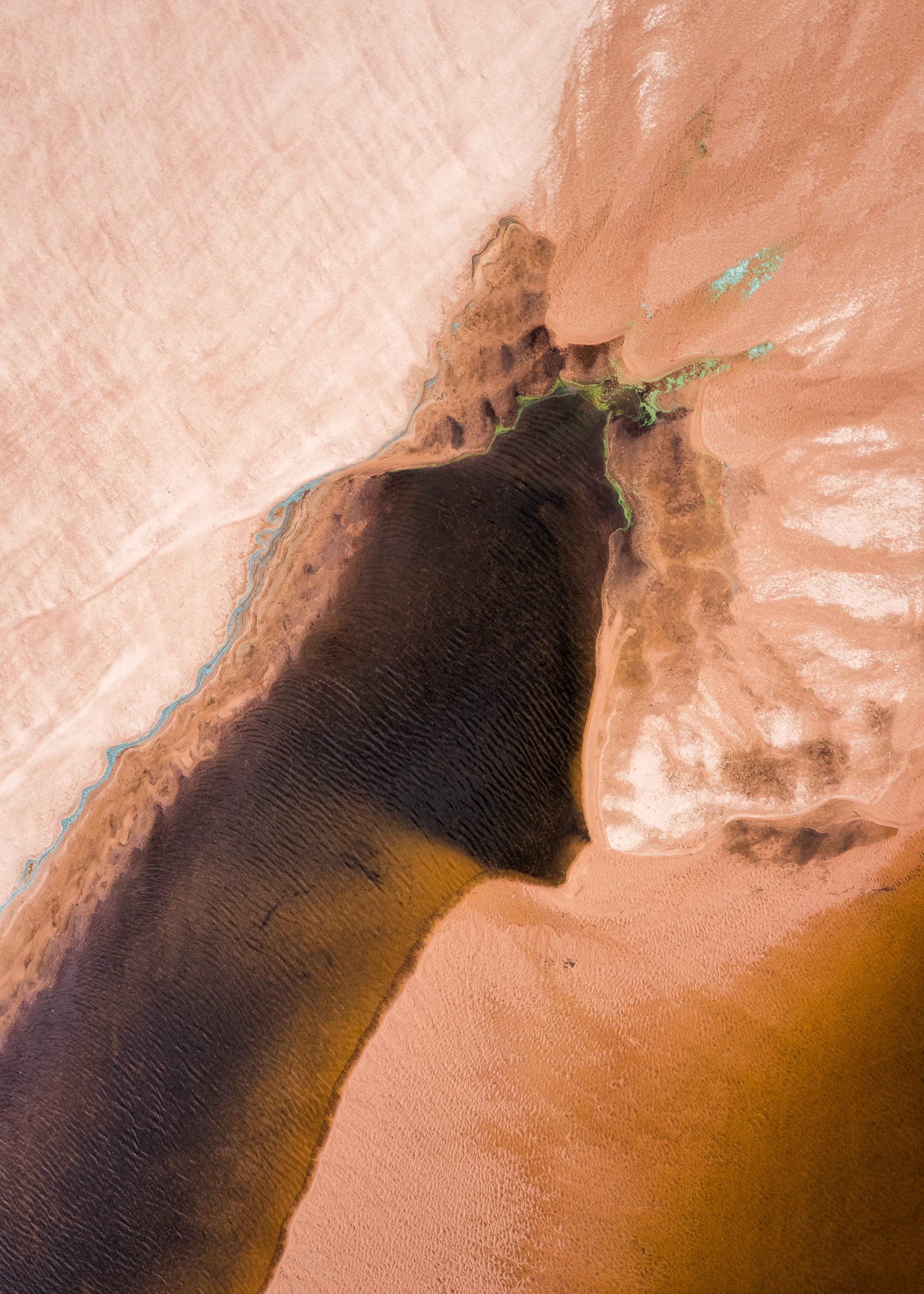

Above Clay Land

Above Clay Land

Sarah Horgan

On True Myth and the Machine Perspective

I know this is true, and my grandmother would concur: for the Christian, death is a transformation, not obliteration. I read an interview with an author who writes ghost stories, who, when asked if she had ever considered her own end, said, “I am excited about the idea that my [body] will go back to the earth. Will I be worm food, will I be a tree, will I be grass? It is something kind of wonderful to imagine.” There are tones of myth, of animism or reincarnation, in this sentiment; it’s reminiscent of the ancient Greek belief that trees and rivers were inhabited by spirits, or the hope of Aztec warriors to become hummingbirds after death. It’s representative of a kind of forgetfulness, a kind of loss, that is clearly demarcated from nihilistic obliteration.

*

My 81-year-old grandmother is going blind. She lost sight in one eye several years ago after a sudden and anomalous heart issue, but last year, her doctor diagnosed her with macular degeneration in the other eye. Soon—there is no way of knowing how soon—she will be fully blind.

I called her as soon as I heard about her diagnosis. I was in Texas, and she was in Arizona with my grandfather on their annual RV trip. They had spent the day doing one of their favorite activities—driving through wild landscapes in an ATV.

“We saw a lot of beautiful cactuses today, and you know, I just enjoyed soaking it all in,” she told me. She didn’t cry when I asked her about her diagnosis, but I wept. Blindness was hard enough for me to consider, but behind that was the lurking prospect of her death, and that was too much. “It’s alright,” she soothed. “It’s going to be fine. I’ll just keep on living, and the Lord will take care of me, same as he always has.”

*

The ghost story writer’s wistfulness for mother nature’s transformative touch embodies a far greater reality, that reality “about which truth is,” to quote C. S. Lewis. Dust to dust, and compost to tree: we do not become nothing. In Greek mythology, transformation meant the death of the body, but the soul lived on in another kind of body, whether as another creature or in the underworld. In the life of Christ, or what Lewis called the “true” myth, bodily resurrection is what awaits God’s children. With this transformation of our bodies and redemption of our souls, meaning is not lost through death. For my grandmother, this means the corruption and failures of her physical body are not things to be feared, because they do not interrupt the purpose for which she was born.

I wasn’t there, so I can’t say at what point in life my grandma developed this perspective—one of hopeful expectation of the fulfilment of true myth. She committed her life to Christ after a providential cross-country move and, shortly afterward, met and married my grandpa at the age of seventeen. They had just finished high school and had $35 between them. Within a year of the wedding she was pregnant with the first of three children; later they adopted two more. She raised horses, homesteaded in a one-room cabin in the wilderness, volunteered with hospice, and welcomed foster kids into their home. She never went to college and never held a job, but her advice when I was struggling to find a job was more desirable than any professional consultant’s.

Her response to her diagnosis was typical of the woman who often warned me as a child that pouting was an invitation for a little bird to come perch on my lip and leave a not-so-nice little present there. Yet I know that my grandma’s life has not been without deep, deep grief. While I don’t know all her experiences of suffering, I can see that she exhibits an unusual respect for the mercy that limits bring, however unfathomable that mercy may be. She doesn’t shy away from death. In fact, years before Atul Gawande’s book popularized the benefits of discussing end-of-life topics, she asked me to write her obituary (I still haven’t had the courage to do it).

After I spoke with her on the phone that day, I was coerced to consider my own view of death. Though my reaction was initially prompted by her blindness, my mind slyly slipped from the loss of a single faculty to the loss of the person. I have often equated blindness with darkness and forgetfulness and death, even though I know, in my heart of hearts, that this isn’t fair to death.

*

The Encyclopedia Britannica defines transhumanism as “a philosophical and scientific movement that advocates the use of current and emerging technologies […] to augment human capabilities and improve the human condition,” which is a fairly milquetoast description. But the definition also states, “The movement proposes that humans with augmented capabilities will evolve into an enhanced species that transcends humanity—the ‘posthuman.’” The transhumanist perspective of life is that it is stochastic and malleable, and that even death can be manipulated.

This is exemplified in the anti-aging startup Jeff Bezos recently invested in, a move that lent itself to headlines like “Jeff Bezos Is Paying For a Way to Make Humans Immortal.” Then there’s the “merge,” which refers to a hypothetical event where AI surpasses human intelligence and the barriers between machines and biological life disappear. According to Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, the merge has already begun. One of his predictions? We become “the biological boot-loader for digital intelligence and then fade into an evolutionary tree branch” as the ancestor of artificial general intelligence (AGI), aka post-human machines. Technology helps humans do things quicker or easier or with less cost or more pleasure, but if the merge fully transpired, it would make bodily infirmity a thing of the past. Humans would no longer age or die because they would no longer live, at least not in the traditional physical sense—we would become un-embodied consciousness.

*

L. M. Sacasas is an author whose writing thoughtfully penetrates the nuances of technology use in society; in The Convivial Society, he proposes a list of better questions to ask of technology than the kind of things that might cross our minds when we hear of the “merge.”

Sacasas’ questioning reminds us that we are impressionable and that technology impresses, in the literal sense of making a mark on us. While it’s tempting to think of technology as something that only affects us in the ways we choose or allow according to our worldview, Sacasas explains that technology has the potential to profoundly influence our perceptions of the world. Certain technologies encourage us to perceive our bodies as things we can control and transform. Sick can become healthy, ugly can become beautiful, difficult can become easy. His questions force us to confront whether we only see our bodies as good enough when our “dirt” is cleaned up with technology.

Interestingly, both true myth and machine share the supposition that the world is less than perfect. Both recognize that humans are flawed and seek transformation for that brokenness. But in the view of the machine, there is no greater story that we are part of, no greater mercy in our suffering, no greater transformation than a poor one that we ourselves attempt. True myth offers an alternative means of transformation, one where the greatest hope lies in accepting our limits. And contrary to popular belief, the sky is not the limit. Dirt is.

*

Ovid’s Metamorphoses opens with a story very similar to the biblical account of man’s origins. In both versions, God and the gods made the cosmos out of wild nothingness, but made man out of dirt. Many other mythologies, including Chinese, Egyptian, Yoruba, and Maori, tell of humans being formed from some mix of clay and water—why?

Dirt is the medium for so many other things—for the habitat of worms, for the growth of roots, for the decomposition of leaves and bones and all the matter that Ovid’s ancient deities had first drawn forth. Still, it is literally the lowliest thing on the surface of the planet—a metaphor for our position of impotence relative to the cosmos. The essence of dirt also suggests a physical reality: that we are created and defined by a higher order of being, and that our matter matters. Being drawn from dust positions God as the gardener and humans as the dry earth for him to transform into rich, lively humus. We are clay; he is the potter. In both metaphors, we are transformed within the bounds of our original design, according to the designer’s will.

In these mythologies, people understood their position, implicitly knowing that the only proper way for mortals to relate to gods was through worship. Worship was the central principle that guided their lives—whether in Ovid, Hesiod, Homer, or Virgil, seeking the gods’ favor, offering them sacrifices and prayers, and obeying their dictates was the binding thread of life, and it is all woven in with the dailiness of physical living: eating, sleeping, having babies, washing, working, being sick, aging. Mythology demonstrates an almost unconscious cultivation of the banality of physical human life, which is so closely intertwined with worship.

Sacasas’s writing is helpful for questioning the ways a particular technology encourages us to perceive the world, shifting our focus from what is possible to what is worshipful. Transhumanist technology seems to disregard the hierarchical god-dirt, divine-human relationship and the inherent limits that reality imposes on humans. The machine perspective seeks not simply the transformation of brokenness, but the transcendence of humanity—a gnostic divorce of the weak body from superior consciousness. Sam Altman justifies the pursuit of smarter and more powerful AI by calling it human arrogance to suppose that we are the smartest beings and “that we will never build things smarter than ourselves.” But his faith in technology is a replacement for faith in God, and his desire to push the limits is not unlike the disregard shown by the giants in Metamorphoses, who made themselves into a tower to try to overcome heaven. Instead, they fell to the ground in pieces.

The difficulty is that our limits today are not brick-and-mortar. Zeus started a war when another god tried to give humans fire, but nowadays no one is throwing thunderbolts at upstart mortals. That makes technological innovation seem more like a logistical than a moral problem (meaning, the biggest hurdle in innovation is not the risk of god’s wrath, but of just figuring out how to do it). But the more ability we possess to do more powerful things, the more it becomes a moral question, and the easier it is to pretend it’s not. The term “the merge” gives an indication that the dissolution of physical limits depends on a slow, subtle shift in perceptions that comes from the daily use of always slightly more invasive and powerful technologies. The author Paul Kingsnorth writes, “Every culture that lasts, I suspect, understands that living within limits—limits set by natural law, by cultural tradition, by ecological boundaries—is a cultural necessity and a spiritual imperative. There seems to be only one culture in history that has held none of this to be true, and it happens to be the one we’re living in.”

*

Greek mythology is full of stories of gods who traveled between Olympus and earth as they wanted, altering their bodies accordingly. Jesus was actually late in history to be gracing the earth with his incarnate divinity. But it would be a major misunderstanding of these stories to think that we too can ascend at will; Transforming a physical body into a heavenly body and having authority over death are the purview of the gods. What the Apostle Paul wrote on this subject concurred with Ovid:

We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trump: for the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed.

The mythic perspective says it is up to the will of the gods to transform and raise up the mortals. It is up to the maker (to Ovid, that was either Prometheus or an anonymous “creator”) to take the dust of a beautiful earth and make it into something that walked with its face upright. In Ovid’s words: “Whereas other animals hang their heads and look at the ground, he made man stand erect, bidding him look up to heaven, and lift his head to the stars.” In the psalmist’s words: As the eyes of servants look to the hand of their masters… so our eyes look to the Lord our God, until he has mercy on us.

*

My grandmother’s attitude toward blindness and death gives an almost uncomfortable answer to the question of how myth and machine affect perception—she accepts that something like failing sight is not an accident of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, but a purposeful limitation set by a God who exists before and beyond human knowledge. Through her losses, my grandmother has shown that she does not rely on the hollow promises of technologies to give her hope (Glasses improve her vision somewhat, yet the weaker her eyesight becomes, the more her ardor for saguaros seems to grow.) She has accepted the temporary mitigation of suffering provided by certain tools, but the fact is, she never had perfect vision. In one sense, she recognizes that she has always been dim of sight—always been limited, always been unable to overcome her own brokenness and sin. Scripture has a word on this too—now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face.

The beauty of this future then is that we are not hanging on the judgment of fickle Greek gods, but we have the promise of a merciful and just God. The risen Christ will enact a glorious transformation in us, in the proper way, at the proper time. Unlike the gods of pagan myths, Jesus didn’t come to pluck the flowers from the soil for his table in heaven, but chose to experience the full range of the dirt life with us. And thankfully, he has promised us a transformation from our designed-to-break-down bodies that makes anything we (or our robots) could come up with pathetic in comparison. In his promise of then, there is hope, not despair, for the day when a tall pine tree folds its hands above the shell of me, that body that groaned for the redemption that the true God finally, finally brings to fruition—a metamorphosis that we cannot exact ourselves.

*

“In eternity this world will be like Troy, I believe,” muses the narrator of Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, “And all that has passed here will be the epic of the universe, the ballad they sing in the streets.” All who were once blind or forgetful or forgotten or mute will be able to see and sing, and the things that once bound broken bodies will be stanzas in a joyous song.

The machine view may be that these words and stories are random amalgamations of data, and the bodies they speak of probabilistic globs of cells. The machine may say that it, too, can spit out a pleasant-sounding song about the end of humanity. But myth is so much more than a collection of words, and what it says of our bodies is far from meaningless.

Take tlaquepaque.

My grandmother doesn’t use her phone much now that her vision is so strained, but when she does message me, it is usually to share her wonder for one of two things: the natural world (pictures of cacti abound), or the English language. We often text each other tantalizing new words we encounter—recent examples being pyrexia, balneary, and tlaquepaque. This last is a Nahuatl word that means “the best of all things,” and when she texted it to me, she said, “Isn’t that magnificent?”

“The best of everything” is a charming way to describe a pleasurable experience of a well-lived life. But the Aztec expression has a prosaic meaning too: “the place above clay land.” The place above clay land was the afterlife where warriors rose with painted wings to circle the sun god in awe. It describes the hope of transformation for people made of dirt who deal in dirt. The first people to speak the word tlaquepaque, who recognized a connection between magnificence and being above clay land, are long gone. But this word tells us how they might have perceived the world: as the imperfect foil to the perfect world beyond. The place above clay land is the manifestation of mercy, the home of God and our transformed, renewed bodies. Somehow, that second definition is even more apt than the first one to describe the magnificent then.

One of the greatest gifts my grandmother has given me is her example of how to live in the dirt world below. Through her life, she has shown me that it’s possible to hope in something I cannot see and to accept the mercy along with the pain. She has exemplified how to use the tools available to humans to worship God and cultivate the dirt he gives us. She has shown me how to view my limited life through the lens of a coming and glorious transformation. Watching her walk both blindly and boldly toward the place above clay land, I think I might have the beginning to her obituary.

Sarah Horgan

Technical Writer & Editor

Photography by Naara Inub