The Bursting Book of God

The Bursting Book of God

Preston Pouteaux

Hidden in the rocks of southern Alberta, there is an archive of our distant past. Most of my neighbors make their living off of this ancient history—working in some capacity for the oil and gas industry. Engineers, geologists and project managers find new ways to drill down to hit the Devonian aged reef complex deep below the surface.

Once, when this area was under water, parts of Alberta were a vast network of coral reefs that, in time, created solid, but porous rock formations. These now hold the condensed and transformed remains of this history in the form of brackish archaic ocean water, and bio-matter like plants, bugs and dinosaurs. In other words, oil and gas. Down the road from us is the Royal Tyrrell Museum, a world-class dinosaur exhibit showcasing all the discoveries regularly kicked up in the Drumheller badlands. The history of my place is deep beneath our feet, but much of it can be found closer to home.

*

“What are you guys doing?” Myra’s bike helmet was tilted and her voice carried a tone of incredulity that is so often belied by her tiny voice. My seven year old daughter, Scotia, didn’t have to look up at the neighbor girl, “We found dinosaur worms.” Her hammer came down again with a thwap on a pebble, oversized safety glasses hanging at the end of her nose. Myra looked down, up at me, then over at the pile of stones we had collected from around the neighborhood, “can I look for dinosaur worms, too?”

Early in our rock-breaking we had found a little brown mark inside one of the more sandy stones. I casually declared that it was a dinosaur worm fossil, and all eyes lit up. Our afternoon fun became a full-fledged expedition, maybe even an industry. My neighbor Eric came around the side of his garage to a small archeological site in our alley, now under the full control of neighbor kids squatting with hammers, tapping away on a growing gravel pile, “what do we have here?” I wasn’t sure—it was mostly the end result of a dad looking to occupy kids on a Sunday afternoon. It eventually turned into much more than that.

On a normal day, we move at the pace of a young family with children as we stroll through our suburban neighborhood and around the man-made pond at the end of our alley. We have time to slow down and look. Pigeons on our roof make me think of the story of the Passenger Pigeon flocks that would darken the sky for days, so numerous were their numbers; long since hunted to extinction. Bees, now in swift decline around the world, are zipping from my little backyard apiary refuge in a persistent and ancient dance with dandelions and willows. And rocks; little Kinder Surprises with their stories to tell from a time before. Suburbia may have laid out its sidewalks and mailboxes, but it is only a scripture-paper thin moment folded over a much older story.

*

This place: the pigeons, the bees, the oil and the dinosaur worms are a bursting book of God. The Belgic Confession says that God is revealed in two books: the written Word of God, and the universe, “before our eyes... in which all creatures great and small, are as letters to make us ponder the invisible things of God.” God, this Maker of all things, has been taking me deeper into this book, where God’s revelation is found in all that is touchable, smellable, hearable, seeable and tastable. I am discovering the ancient, the sublime, the cosmic and the subatomic.

Still, I did not expect that God’s loving and creative craft could be found in the rocks too. I had not imagined such an ancient and abiding presence in my neighborhood, in the pavement, playgrounds and façades of homes along my street.

We do not see most of what is right before us. Eugene Peterson writes that, “Our senses have been dulled by sin. The world, for all its vaunted celebration of sensuality, is relentlessly anaesthetic.” Could Peterson be right? Could it be that the world, with its apps, Google Maps and scrolling shopping malls filled with alluring distraction is actually lacking sensuality? For all the sensory overload, we are a numb people.

A vehicle collision at an intersection is merely a novelty on the way to work, the trees and parks are just the backdrop. The noise in our head is now expected and endured, and phone alerts do not alert us anymore. Anaesthetized to the story, the clamor numbs our senses like an overlay. We may no longer reel, but neither do we feel. The paraclectic poetry of a world set before us by the very hands of a loving-present-creative-God is lost to our imaginations, rendered down to a slumbering hum; narrowed to categories and degrees of usefulness. But there, in the back alley, is the Spirit of God inviting us to see anew. The “thwap” of a child’s hammer on a rock is the surprising antidote for this anaesthetic. The microscope, the library card, the binoculars and the margarine-container-turned-bug-zoo are all the awakening stuff of faith. The opposite of anaesthetic is aesthetic. The opposite of numb and sleepy is beauty and wonder at the sublime. Consider that in a “relentlessly anaesthetic” world, we have the means to wake up again: we are given beauty. Art. Music. A spouse. Tulips. Bees. Story. Kids. Neighbors. It is everywhere and the more we look, the more we see. Beauty tends to life even in spite of those forces that deal in destruction. Beauty awakens, vivifies and beckons us.

*

Lina Verovaya

For much of my childhood, the living world was mostly non-essential and secondary to the more elevated concerns of discipleship and faith formation. Mountain vistas may have served useful to inspire prayer, but I had no imagination for the landscape I ran through on my way to school each morning, let alone the people next door. When I was a boy at camp I felt the presence of God when I prayed for a shooting star, and saw one. It was a miracle. Not the meteorite—I dismissed that in favor of the spiritual significance of the moment.

I did not yet have an imagination for reading this book of God found in the unfolding world around me. I received a burdensome gift with my introduction to faith: a skepticism of the natural world, wrapped unwittingly in gnostic tissue paper. It is the ever lingering, bifurcating vision of a Christian life separate from the world and always uneasy with the skin we are in. It ultimately leads us to sequester from the poor, the other and the neighbor. It distrusts history and science, it leads to a blurred vision of Jesus at work in all time, and cannot come to terms with the immanent presence of God tending to seeds, bees and those on my street. Faith that extricates us from our natural world may have handed us a one way ticket to heaven with the “amen” at the end of the sinner’s prayer, but it cannot explain what on earth we were supposed to be on about here and now, in the first place.

This world is ancient, storied, discoverable and a stunning mystery to me. Instead of coddling a position that separates inquisitive wonder from Christian faith, I am learning to ask all the more in the presence of God. I have found great peace here. Walking with God into God’s world, and into my neighborhood, to ask in wonder about the beauty I see is where I find life, and have come to Life. Learning about the ways of God are complex in an elegant way, like biochemistry or astrophysics are seen beautifully in a flower or a starry night; simple and yet endlessly enigmatic the deeper you go.

God should be all the more—both sublime in my awe and personal delight, richly complex and way beyond me. I can be certain about much, and absolutely astonished by even more. I am now far more comfortable to stand in silence at the grand horizon of the life of Jesus and His profound love. There’s safety here.

*

Some evangelicals are in a process of deconstructing their faith. The growing breadth of information, opinions and even personal disappointment or heartache have brought some to dismantle portions of their faith. Once a solid rock to stand on, now, for some, a pile of gravel. Some stand by and wonder if their beliefs were built on anything at all.

But this has not been my path. The cynicism that might very well have stopped me has presented in my life as inquisitive wonder, relational peace and a longing for beauty. Each stone is something worth opening. It is a celebration founded in God’s first response to creation, that “it was good.”

Walter Thiessen, in Glimpses of a Good Life, writes that “celebration is the first and foundational orientation toward life.” The Creator God has come in the incarnation story of Jesus, and then as though with a filioque-surprise, the Spirit meets me here again in the beauty of this co-creative relationship of love. “Beauty will save the world,” wrote Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Beauty, it seems, has also gone about saving me.

The dinosaur worms may be just a brown line in a sandy stone, but for those who crack away in discovery, they are evidence of the faithful creative work of a present God who has long been telling God’s story in every place. From my back alley, to my apiary, to my garden and front porch, my home is set amidst the grand story of God’s declaration of goodness. This place is alight with God’s beauty, from grass peeling upward through the asphalt to neighbors striking a match against their BBQ, each a story of love.

Thwap. Thwap. C-r-a-c-k.

“Dad! Look! It’s amazing!”

Preston Pouteaux

Writer & Pastor

Preston has been published in Faith Today & The Chestermere Anchor and the author of The Bees of Rainbow Falls & The Neighbours Are Real

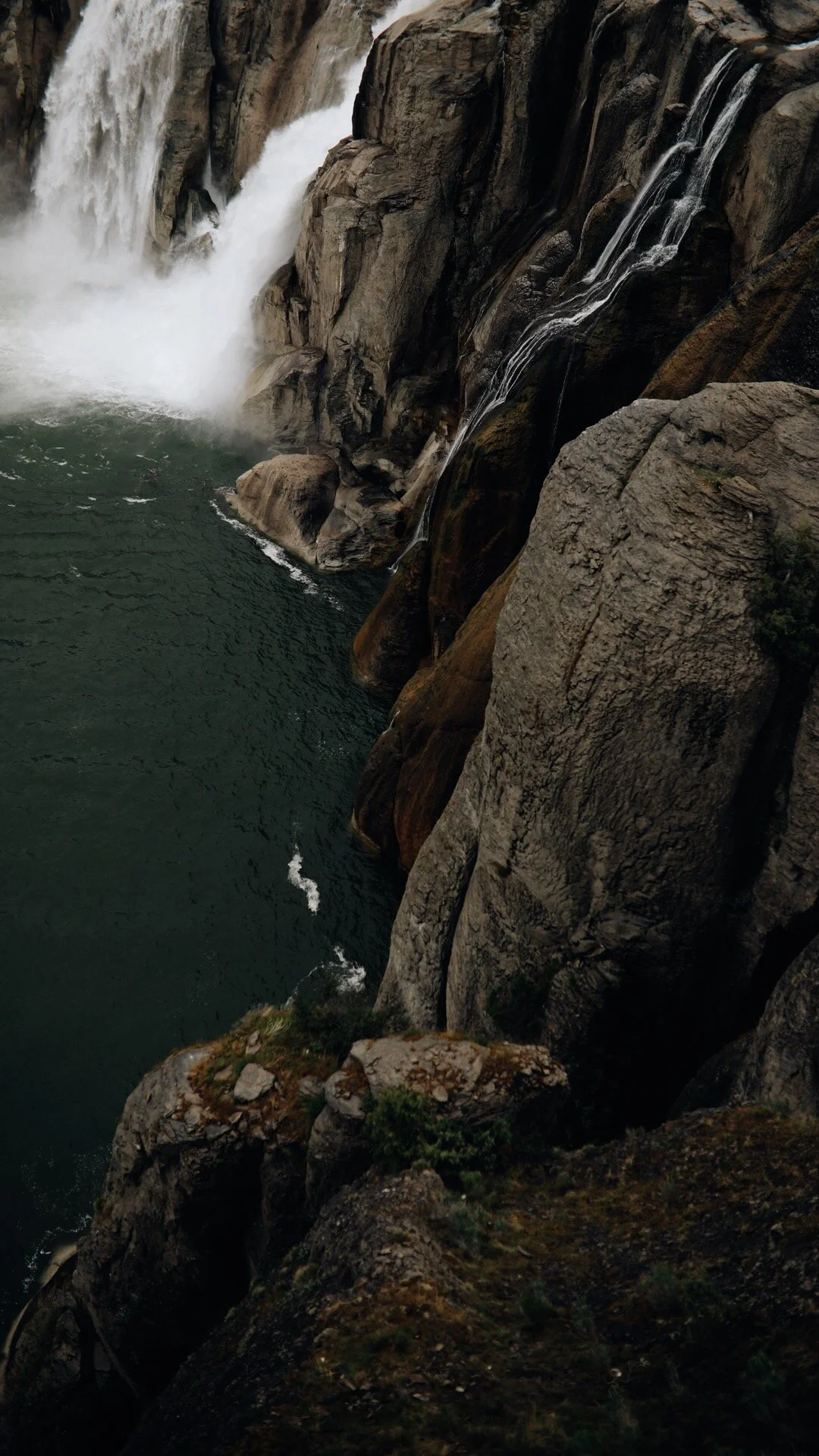

Photography by Philipp Pilz